Minimalism

It has been ten months, since I fully unpacked. Since April of 2015, I have been living out of two bags. After some life changing events, I left the amazing city of Wellington, New Zealand. It was truly the most beautiful city I have ever lived in. After spending two and a half years there with some very amazing people, my journey led me westward through Australia, Asia and Europe. I met up with old friends, found new loves, and learned the hard and true virtues of minimalism.

The Journey

When I turned in my resignation, people had trouble understanding exactly where I was going and what I was doing. When I mentioned I was “going on sabbatical” one person asked me, “Where is Sabbatical? Is that a local company?” It was difficult for people to comprehend that I wasn’t leaving for a new job or opportunity. After working the standard forty hour workweek for nearly a decade, I was taking a break.

“…right now we spend about in the first 25 years of our lives learning, then there is another 40 years that’s really reserved for working. And then tacked on at the end of it are about 15 years for retirement. And I thought it might be helpful to basically cut off five of those retirement years and intersperse them in between those working years. (Applause) That’s clearly enjoyable for myself. But probably even more important is that the work that comes out of these years flows back into … society at large, rather than just benefiting a grandchild or two.” -Stefan Sagmeister1

I had the goal of traveling while contacting professors about PhD programs. I’ve always wanted to re-enter academia full time ever since my first job after graduating from University in 2005. My previous attempt met with failure, as I was applying to schools in 2010 while the world was still recovering from the financial collapse, and schools were flooded with people looking to re-enter academia. Even though I had a masters degree, my grades and lack of publications set me back against other candidates. This time, I had three publications, one which I was second author on, thanks to a research project I volunteered on with a friend (who has since received his own PhD). The lack of responses I received this time around made me wonder if I was running into the typical case of professors never responding to e-mails, or if my messages were simply going straight to spam.

I learned the world is not suited for nomadic people. The name and address of a hostel was usually enough for custom agents, but for any formal documents I found myself calling upon friends to ask if I could use their address. I was humbled by the constant challenge of language barriers, and found it sad that those in the English speaking world do not commonly learn, much less master, a second language. In many countries in Europe and South East Asia, people typically know at least two, sometimes three languages.

Safe and Sound

“Security is a kind of death, I think.” -Tennessee Williams, The Catastrophe of Success

I cannot count the number of times I’ve heard the words “I’m jealous” and “you’re brave” from various people, in reference to my travels. I moved to Australia, partially because I was depressed, and also due to general unease with the state of the patriotic empire I lived in, more so than a sense of adventure. A good friend of mine once said, “You realize this won’t solve all your problems right?” when I left my home town for the Midwestern United States. Even though I knew he was right, I still felt I had to try.

“…a staggering proportion of human activity – in politics, business, and international relations, as much as in our personal lives – is motivated by the desire to feel safe and secure. And yet this quest to feel secure doesn’t always lead to security, still less to happiness. It turns out to be an awkward truth about psychology that people who find themselves in what the rest of us might consider conditions of extreme insecurity – such as severe poverty – discover insights into happiness from which the rest of us could stand to learn…in turning towards insecurity we may come to understand that security itself is a kind of illusion – and that we were mistaken, all along, about what it was we thought we were searching for.” -Oliver Burkeman, The Antidote2

It’s really not difficult to pick up and leave. Except if you have children, or a mortgage, or a family, or a deep need for a sense of security. We live in a world that seeks to keep us with leases, car payments, student loans and perpetual debt. We live in a lock-in society where permanent addresses and a house full of things make us feel as comfortable and secure as much as they make us feel trapped. Selling and giving away all of ones things is a lesson in the actual value of our possessions. That expensive TV, purchased less than a year ago, fetches a fraction of its initial value on eBay or Craigslist. I’ve learned that whenever possible, it’s better to buy stuff used. Better yet, wait for people to throw things away.

Love

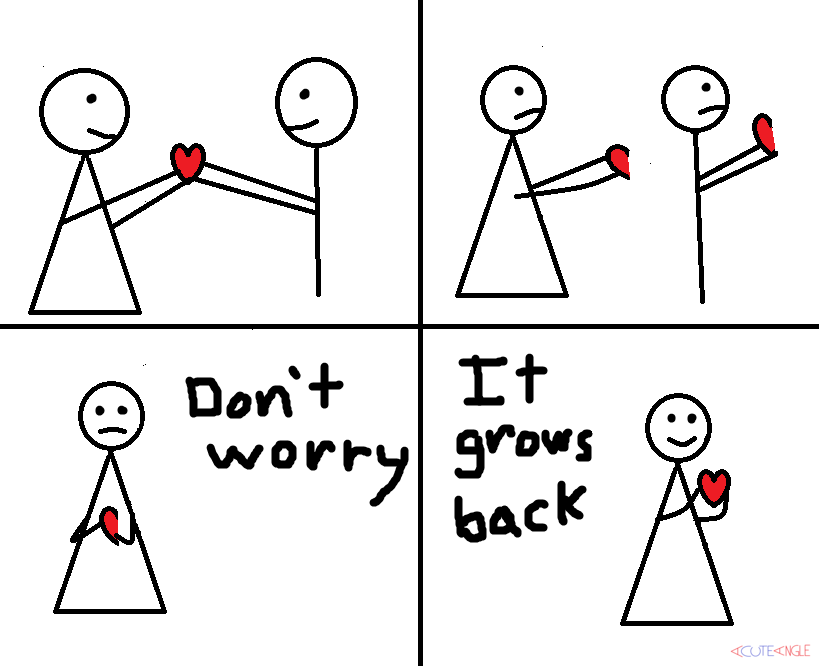

I have never been good with women. I remember having the general feeling that if I could only find a good stable relationship, I could deal with all the other troubles of the world. I hated the clichés of advice, thrown about like a record on repeat, about how I needed to be “Okay with myself” as if human beings didn’t have biological needs or that we weren’t social mammals. Even before leaving the States, I started to explore the concept of polyamory – the idea that human beings can love more than one person romantically.

In building loving relationships with some very amazing women since I left the US, I’ve found that my old belief in the quest for relationship stability no longer felt like the driving force for universal happiness. There were enough tears that they could drown a fish as I boarded a boat, or a train and eventually a plane as I felt I was continually leaving someone who I had fallen in love with.

Where once I would have looked back and only found sadness at what was lost, now I can only feel happiness, not at what I had, but what I feel as if I still have. In changing the way I look at love, friendships and relationships, I feel a deep sense of connection with everyone who has made a deep impact on my life, whether it be romantic or otherwise.

Home

In early January, I arrived in Seattle, Washington. Like the three previous cities I lived in, I had never visited it before deciding to make it my home. After a long journey, I had some amazing friends who gave me places to stay as I searched for work. For two weeks I stayed in a house deep in the suburbs about an hour from the city via bus. I was greeted every morning by Onyx, the sweetest dog whose friendship only required an occasional strip of bacon. The thick carpet under my feet and modern kitchen erupted feelings of nostalgia of my youth in my family home, growing up in the suburbs of Tennessee. It was an odd juxtaposition; the carless backpacker with a mohawk living with young professional suburbanites.

As I continued interviewing at various places, I moved closer to town to stay with a fellow traveler who I met in New Zealand, and who had, like myself, spent nearly a year working and living in Melbourne. I spent a few weeks in a basement room in a cozy little home, filled with two cats, nestled in a city that was slowly being gentrified by the rising housing costs around it.

Minimalism

“You buy furniture. You tell yourself, this is the last sofa I will ever need in my life. Buy the sofa, then for a couple years you’re satisfied that no matter what goes wrong, at least you’ve got your sofa issue handled. Then the right set of dishes. Then the perfect bed. The drapes. The rug. Then you’re trapped in your lovely nest, and the things you used to own, now they own you.” -Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club

Even before I left the US, whenever I moved, I always held to a philosophy of minimalism (mostly because I’m cheap – an attitude passed on to me by my parents, who grew up in poverty). My homes have always been filled with furniture and cookware from Craigslist, thrift stores, Ikea and things left behind by past roommates or thrown out by other university students. Even today, I buy things in terms of knowing I won’t have them forever.

When I first started traveling with just two bags, I felt free and liberated. During my poetry tour around Australia, I met up with a friend in Perth who had been traveling as well. I didn’t truly understand his complains about hostel living and dorm room beds until several months later. Towards the end of my journey, the traveling did begin to wear on me. I looked forward to the moment where I am currently: unpacked.

Although the journey was long and tiring towards the end, I took a lot of timeless photos, learned a lot about language and culture and met some truly amazing people. I feel like I’ve made up for years of unspent vacation days in one year long gap. I could decide to settle, buy a house and join the world of adults locked into their office jobs and mortgages, but the idea of that doesn’t sound remotely tempting. I don’t see it as a failure in an attempt to return to graduate school, but as an experience that helped me learn about myself, love others and work on my own projects.

“I’d flip through catalogs and wonder: What kind of dining set defines me as a person?” -_Fight Club_ (1999 Film)

I will admit the temptation to return to the consumerist world is a strong one. We live in a society built around entertainment in advertising. There are times when I miss driving, but I don’t miss the money and effort that went into car ownership. I miss the sound of music I have collected from around the world playing though a fine set of high quality speakers–knowing that if I do purchase a sound system from a pawn shop, it was probably loved just as much as the person it was stolen from. I love technology and the tools that help me work on projects and research, but I realize useful tools are often sitting around in peoples’ basements collecting dust.

I want to enjoy the things I can afford, realizing they are things I own without letting them own me. I want to use what I’ve learned, not to enter the workforce once again as just another drone. Rather I want to use my experiences to enjoy what I have and be more prepared the next time I embark on a new journey.

-

The Power of Time Off. July 2009. Sagmeister. TED. ↩

-

The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking. Burkeman. p129 (Kindle Edition) ↩